November 14, 2017

- We can be irrational investors and have to be aware of our biases.

- Investing biases can cost us significant returns over time.

- Group Thinking, Loss Aversion, and Overconfidence are few of the prominent biases we possess.

- Systematic Investing diminishes the bias related underperformance evident in Active Management.

- Biases can be hard to eliminate but can be managed to improve investment performance.

Recently, we wrote about how Systematic Investing Works Great and the growing body of research which provides evidence to the superiority of models and algorithms in decision-making versus relying on expert judgment of active managers. In the article we compared two Graycell quantitative portfolios with index benchmarks, (a) the Graycell S&P Quant Portfolio with the S&P 500 index, and (b) the Graycell Small Cap Quant Portfolio with the Russell 2000 index, demonstrating the significant risk-adjusted excess returns of quantitative portfolios over benchmark indexes.

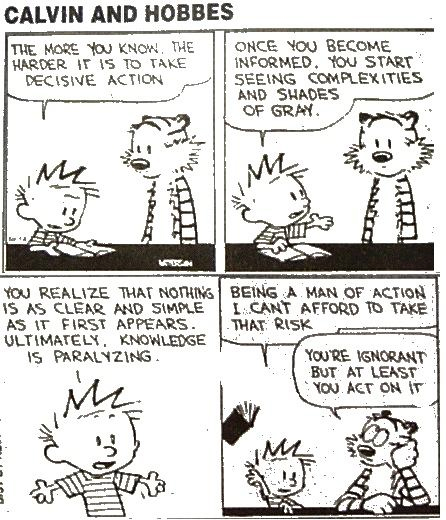

One of the key reasons that quantitative portfolios are well-positioned to outperform active management, in which money managers or individual investors buy and sell positions based on their company analysis, is the mitigation of behavioral biases.

What are Biases?

Behavioral biases are our tendencies to react in a certain way. Such tendencies are embedded in our thinking and influence decision-making to a significant extent. These biases are the mental short-cuts, important to speed up our thinking and reduce cognitive load, and often times our biases save us time and energy.

Along with the natural cognitive biases, we are also influenced by the pool of emotions and experiences accumulated over our lifetime, which create certain proclivities in our thinking. We lean on these preferences to aid our decisions and judgments.

All these cognitive and emotional tendencies are collectively referred to as behavioral biases. These are the subjective elements of our decision-making, the ones which we possess by default.

Biases and Investing

Making rational decisions was not really a priority on the plains of Africa as the human species evolved a few million years ago. But surviving the day from the lions and other threats was a priority, and instincts and biases became imprinted on our mind, in place of rational analysis, to boost our survival chance.

But there are times when our inclinations can result in irrational or unproductive decisions. Investing is one area where behavioral biases can significantly hurt our investment returns.

Psychologically, our opinions are filtered through our biases. This creates irrational choices and prevents sound decision making, particularly when decisions involve investing, money, time constraints, and emotion. As Richard Thaler, 2017 Nobel Prize winner for his work in behavioral economics, has observed that humans are predictably irrational.

We are prone to over-or under-estimating, being overconfident in our analysis while doubting data contrary to our opinions, and using perceptions to create or fill-up what doesn't exist. Our decisions are not always rooted in facts, logic, and reason.

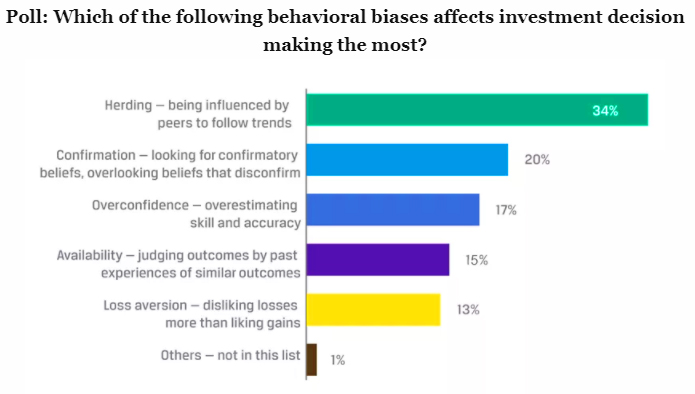

A 2015 survey of over 700 financial practitioners by the CFA Institute revealed some of the biases affecting investment decision-makers.

Biases can interfere with optimal judgment. By being aware of these biases and mitigating them, investors can work towards arriving at more objective and rational decisions, leading to enhanced portfolio performance. This is easier said than done, and behavioral bias is an issue that affects everyone from individual investors, to traders with multi-million dollar positions for banks, to portfolio managers responsible for investing billions of dollars.

No wonder even Benjamin Graham, considered the Father of Value Investing, observed:

These behavioral biases to a meaningful extent explain why many active managers are unable to outperform standard industry benchmarks like the S&P 500 (SPY), Nasdaq (QQQ), Russell 2000 (IWM) and Dow Jones (DIA). This has led to net cash outflows of over $500 billion in the 10-year period from 2007 to 2016. At the same time, quantitative and passive management has experienced growing cash inflows.

We have to accept that we are simply not the rational investors that are assumed in theories and hypotheses, like the Efficient Markets Hypothesis. People develop biases in the normal course of life, which creates irrational investors and market inefficiencies.

Quantitative models have an edge because computer algorithms simply don't feel and react the way humans do.

Kinds of Investor Related Biases

There are many biases that researchers have identified. However, we cover only a few of the key behavioral biases that investors should be aware of as they manage their portfolios.

Cognitive Bias. In general, most biases listed here can be a form of cognitive bias, which is a systematic pattern of deviating from rationality in judgment and arriving at decisions illogically.

An example of a cognitive bias can be when an investor avoids biotechnology or technology sector exposure in their growth-focused portfolio for they are perceived to be volatile, even when a risk-adjusted performance evaluation of these sectors may offer a compelling case for investment. The cognitive bias here is leading to an illogical interpretation, irrationality, and inaccurate judgment.

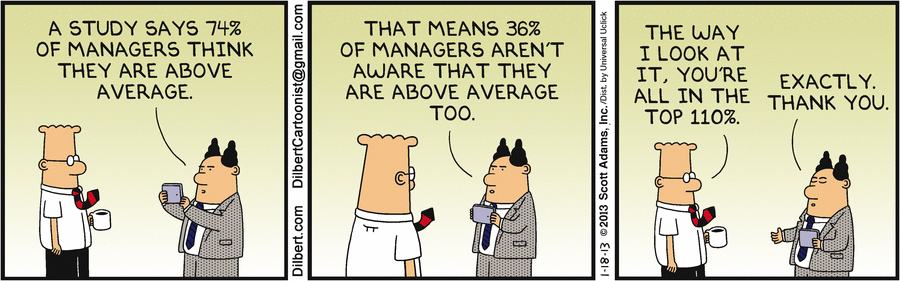

Overconfidence Bias. Investors have a tendency to be overconfident in their own abilities. A few short-term successful trades can entrench such a perception, and cloud our judgment. It is very easy to overestimate our analytical abilities. It is harder for an individual investor to have superior access to information and analytical resources than a full-time professional investor, and even professional investors struggle to beat the benchmark indexes. But overconfident behavior in investing is common and leads to short-term excessive trading and poor record of investment returns over long-term.

Interestingly, this tendency to be overconfident is exhibited more in males. In a research paper titled "Boys Will Be Boys: Gender, Overconfidence, and Common Stock Investment," published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics by University of Berkeley professors Brad Barber and Terrance Odean, it was revealed that based on their research of a sample of 35,000 individual accounts over a six-year period, males are not only more overconfident when it comes to their investing skills, but they're also more short-term oriented and more trading-intensive. To add further insult to the male investor pride, all this trading revealed that they also tend to sell their stocks at an inopportune time for higher total trading costs including tax implications. Women are more amenable to a buy-and-hold approach. As we can see, there is a gender bias as well when it comes to investing. The bottom-line was that the more active the investor, the less money they made.

The overconfidence bias can be managed by recognizing that we compete in the market against well-informed professional investors. Trade less and invest more, resisting the consistent urge to believe that this time your information and analysis is superior to others in the market. Value counter-opinions, especially if they are scarce.

Loss Aversion Bias. Ever felt the relentless pressure of a losing position, but an inability to take the loss. This is an example of an emotional bias, generally referred to as the Loss Aversion Bias. As long as we don't sell, we're not taking the loss. And that keeps us in a losing position, perhaps even leading to growing losses which are eventually recognized. Research has revealed that our desire to avoid a loss can be so intense that an investor will be willing to take even more risk with the hope of eventually avoiding such a loss, by adding to a losing position and attempting to average-down their cost-basis. This may be a prudent strategy in some cases. But which cases it works is a very hard judgment call, and quite often it can work against us.

Loss Aversion is an insidious bias that many investors experience with potential long-term adverse effects on the portfolio. Behavioral economists also refer to it as the Regret Bias, since we engage in illogical and risky behavior to avoid the feeling of regret of being wrong and incurring a loss.

I have encountered the Loss Aversion bias many times. In fact, most investors will face this bias at some point. It appears that sometimes the more you get to know the company, the harder it can become to wind-out when the investment begins to turn sour. Part of the aversion comes from having to give up on a well-researched investment.

This is a hard one to overcome and professional investors have to be constantly on guard with this creeping bias. I decided to shift to clearer rules, and let systematic investing guide me. Even for active investors, this bias can be managed with a well-defined investing system with strict investing and trading rules to preserve objectivity. The hard part is to stick to those rules, a behavioral change that sets in with the experience of hard knocks. This is where the computers win over active investors, for the machines follow the rules - at least for now.

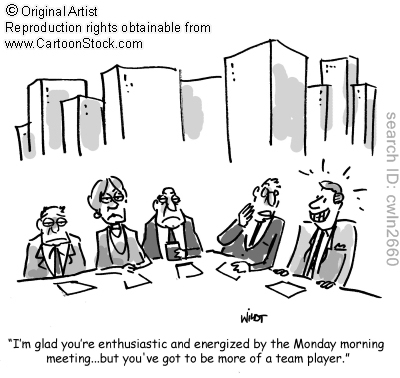

Bandwagon Effect or Herding Bias. We gravitate towards group-think. Humans have a very strong desire to be part of a herd. During the early years of evolution, that ensured survival on the wild plains. Even now, social-based community opinion guides us in our thinking and spending decisions. However, the herd or group mentality doesn't always lead to rational decisions in investing.

Perhaps Warren Buffett had this bias in mind when he advised investors to be greedy when others are fearful and fearful when others are greedy.

This bias was visible during the Internet boom-and-bust in the 2000-2001 period, the housing and financial crisis in the 2007-2009 period, and even the Chinese stock market that has experienced multiple boom-and-bust cycles over the past 10 years. It gives us comfort to know that our friends and chat members are also invested in the same companies. Strength in numbers doesn't always work out in investing if we don't have rules to protect us from the downside.

Overcoming group-think bias can be hard. Even when we are losing, it's hard to abandon the consensus. However, being aware of the bias and recognizing that each investor has unique financial objectives is a way to avoid taking the easy way of following the crowd. Going with the flow begins to subdue our own analytical thinking. One can fight this bias by limiting the exposure towards crowd-sourced ideas to a smaller portion of the portfolio. If things work out, that's great. But if not, it won't cripple the portfolio.

Disposition Bias. Ever experienced the tendency of selling stocks that have appreciated in value (winners), while holding stocks for too long that have declined in value (losers). The bias of selling winners too early while holding losers too long is referred to as Disposition Bias. It's closely related to the Loss Aversion or Regret Aversion bias discussed earlier. Researcher Andrea Frazzini, during her time at Yale University, found out that the bias ends up creating a post-event drift higher when the news is positive. The reason is that many investors exit around the same time on a rising stock, thus leading to the stock not reflecting the positive news immediately. Consequently, the stock drifts upwards with a higher predictability in the weeks following the event. The reverse is true when there is a bad news event, as the average-down crowd buys preventing a fairer correction, and consequently, the stock drifts lower over time.

Besides hurting the returns, this bias can also create sub-optimal tax implications. The old Wall Street adage of "cut your losses and let your profits run," can perhaps assist investors in developing the discipline to manage this bias, and achieve the decision whether to hold or dispose of with greater objectivity. As the winners grow, rebalancing or trimming the positions is also a key portfolio management rule recommended by professionals, although personally, we don't pursue that in our adequately diversified quantitative portfolios.

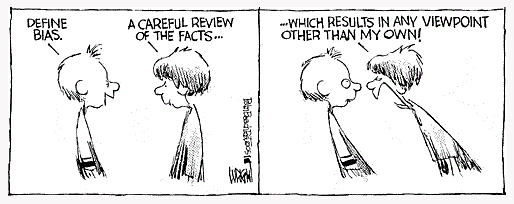

Confirmation Bias. It happens many times to all of us. Ever observed yourself gravitating towards an opinion which is in sync with our belief. It could be as harmless as watching a news channel that is more aligned with our political opinion and confirms our viewpoint or can be potentially harmful when we look for information that only confirms our investing hypothesis while ignoring alternative arguments that do not confirm our opinion. You must have encountered a community stock board where an opinion is largely one-sided, and everyone gangs up on a counter-opinion that may show up. This is the world of Confirmation Bias.

Investors believe they are objective in evaluating facts. But often times, once we arrive at a conclusion, we only seek out evidence that confirms and validates our opinion. The tendency to test and evaluate ideas in a one-sided way and ignoring alternatives can have an adverse effect on our investments.

This bias can exist without us being aware. One thing that can contribute to managing this bias for investors is to seek out multiple sources of information and make a deliberate effort to learn about counter-points to your thesis.

Anchoring Bias. Ever encountered a situation where you see an item on sale but don't buy, and then on a subsequent visit, you find it hard to purchase that item at the regular price, for our reference is the initial sale price. Well, I have often experienced this bias in investing. It is hard to purchase a stock at $25 when you saw the stock price at $20 a week ago, and often times you will simply wait for a pull-back to purchase at a price closer to the Anchor price in your mind. In this situation, we have anchored our judgment to the first piece of information that became embedded in our mind.This is an example of Anchoring, a tendency where a certain piece of information gets anchored in our cognitive process and affects subsequent decision-making.

A car salesperson sets an initial price, which becomes the basis for the rest of the negotiations. As the salesperson discounts the price further, anything lower than that initial price begins to look more reasonable, even if the price is still much higher than what the car is really worth.

Investors who experienced the economic crisis of 2007-2008 with fierce stock market declines developed a bias against stock investing which kept them on the sidelines even when the markets recovered and continued to move higher. As the markets rose, the Anchoring Bias drifted them towards an underweight in equities, holding back the portfolio performance.

Anchoring needs strong discipline to overcome and requires a more open mind which evaluates a wider range of investment options.

Activity Bias. This is more of my personal experience bias and may be related to the Overconfidence Bias discussed earlier. At one time, engaging in portfolio activity meant to me that I was doing something concrete in managing my portfolio. It was hard to leave positions alone, giving them time to grow. I had the urge to jump between positions too much and realizing at the time of tax filing how ineffective an approach it was. It is important to not confuse activity with performance. Let a change in thesis call for a change in investment position, not the daily swings in prices. The thesis could be driven by technical or fundamental factors. It is important to have your own investing system with the risk tolerance levels you are comfortable with. Then possess the discipline to remain within the system that you set up to protect yourself.

Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathway and long-term investment partner of Warren Buffett, refers to these multiple biases and tendencies acting at the same time in the same direction guiding us towards an irrational action as the "Lollapalooza effect." In his book, Poor Charlie's Almanack, Munger talks about a number of cognitive biases that we should be aware of in order to make better decisions. For investors willing to delve further into the subject, Mr. Munger delivered a thoughtful and often-cited speech, at the Harvard University in 1995 titled, Psychology of Human Misjudgment, which can be read here, and the audio can be heard here.

Conclusion - Be Aware and Manage, if Not Overcome

These are only a few of the biases that investors encounter.

Achieving the investment return objective is a function of both investor's analytical work, as well as the management of investor biases.

The best way to overcome biases and control our tendencies that harm investment performance is to pursue an investing system, adapting the system when necessary, and working hard to ensure not to deviate from the system. Being aware of the biases can help in monitoring and diminishing them, even if not eliminating them.

Discipline remains the key to a long-term, successful investment strategy. About 80% to 90% of the money managers are unable to outperform benchmarks over a 5-year period. Human biases significantly contribute towards holding back active management returns, when compared to passive and quantitative strategies.

Model-driven systematic investing is one way to mitigate the behavioral biases that affect decision-making in active management. and also keep trading costs lower.

Perhaps it was one or more of such biases that made Ben Graham, above, talk about the investor fallibility, as well as Warren Buffett recognize the biggest handicap towards being a successful investor when he noted:

Greater awareness may just help an investor to discover and stay invested in some of the great names of the future, just like the storied stocks of Amazon (AMZN), Apple (AAPL), Google (GOOGL), Facebook (FB), Netflix (NFLX), Microsoft (MSFT), Priceline (PCLN), Regeneron (REGN), Amgen (AMGN), Baidu (BIDU), Incyte (INCY), Dollar Tree (DLTR) and Exact Sciences (EXAS) - few of the top performing stocks of the last 10 years.

The article was first published here on Seeking Alpha...